2

Welcome back to Baseball by the Numbers. Today we are looking at uniform number 2. Like number 1 there were a lot of players in history to wear number two. My list has 664 total players. Out of that group ninety-five of those (14.3%) had the number for over five years, with eighteen of those having worn it for ten plus years. For career WAR, twenty-nine players who wore number 2 had a career WAR over 40. So, taking that big number 664 down to seven was much easier once I factored in all my criteria. What wasn’t easy was choosing the number one player. Not because he didn’t deserve it, but because of the team he played for. I’m sure many of you already guessed who that is…

Number 1:

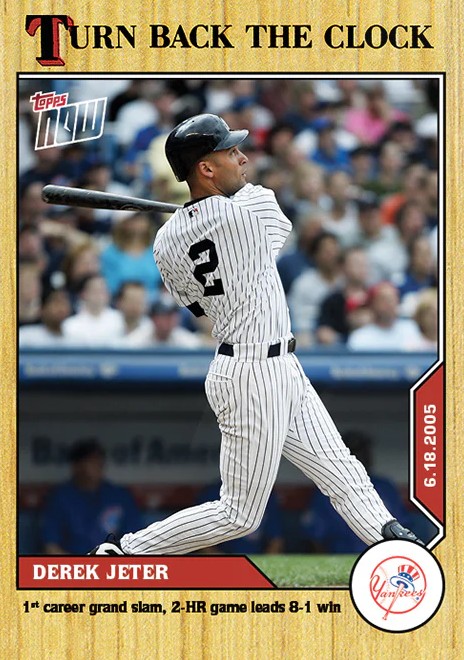

Growing up, I despised Jeter. Booed him on TV and booed him at Fenway Park. Traded all of his cards (big regret). He was the enemy, and I was not having any of it. The funny thing is, as I was making this list, I was ready to find a way to not put him in the number one spot, but I just couldn’t. Derek Jeter was a stud, pure and simple. He was a star and a leader and I’m not that same kid anymore, so I can say it…even with a little trepidation.

Derek Jeter played shortstop for twenty years in the Majors, all of them with the Yankees. During those twenty years, he has always worn number 2. From 1995 to 2014 “The Captain” was one of the best to play the game. He holds many Yankee records including hits (his 3,465 place him sixth all-time in MLB history), doubles (544) and stolen bases (358). He was a major part of the Yankees late ’90s dynasty, contributing to their World Series wins in ’96, ’98, ’99, ’00 and ’09.

The card I used is the Topps Now Turn Back the Clock. It’s a great card, in the style of the 1987 Topps set, one of my personal favorites (which I say all the time about so many sets lol). The wood borders, the logo in the corner, and most important his uniform number front and center. Great card for this series.

Jeter was ROY in 1996 after hitting .314 with a .370 OBP, 10 home runs, 25 doubles and 183 hits. He would continue his stellar play throughout his career, adding fourteen All-Star appearances, five Silver Sluggers and a World Series MVP award in 2000. He also played fantastic defense, with five Gold Gloves.

Jeter ended his career sixth all-time in the Majors with 3,465 hits. He had a career .310 batting average, 260 home runs (sixth all time at shortstop), 544 doubles (first all time at shortstop) and 1,311 RBIs (third all-time at shortstop).

He was also a clutch player in the playoffs. While working toward his 5 World Series rings, Jeter had a career .309 postseason batting average, holds MLB postseason records for hits (200), singles (143), doubles (32), triples (5), and runs scored (111) and is fourth in postseason home runs with 20 and RBIs with 61, fifth in walks (66) and sixth in stolen bases (18).

Jeter was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2020 with the second most votes in history at 99.7% on his first ballot.

His number 2 has been retired by the Yankees in 2017.

Number 2:

I love it when we get to these Golden Age players. Charlie Gehringer played second base for nineteen seasons from 1924 to 1942. Like Jeter, he spent his entire career with one team, the Detroit Tigers. He wore uniform number 2 for eleven seasons, which was most of his career. We must consider that most teams in the MLB didn’t wear uniform numbers until the late ‘20s early ‘30s. It looks like Detroit started around 1931.

Gehringer has the highest career WAR for those with the number 2, coming in at 84.8. His nickname, “the Mechanical Man”, is very cool, almost futuristic. I honestly debated putting him at the number 1 spot but had to keep my Yankees hate in check. Not that Gehringer didn’t deserve it, but Jeter just edged him in a few places.

Gehringer was a quite player from a small town. A man of few words, Gehringer’s speech at a banquet in his honor was one sentence, “I’m known around baseball as saying very little, and I’m not going to spoil my reputation.” (Bak, 1991)

I love that quote, and it’s an example of why I love these Golden Age players. Baseball was raw, it was unfiltered, it was a Western, with silent heroes carrying bats and gloves instead of pistols. If Gehringer played today I could see an interview where they ask, “Tell us how you got on base so much. What’s the secret?” and him smiling in reply, “I hit the ball.” I just love that a skinny, small town, quiet kid could come to Detroit and become a standout star. Not showing off, not mouthing off, just playing the game he loves to the best of his ability.

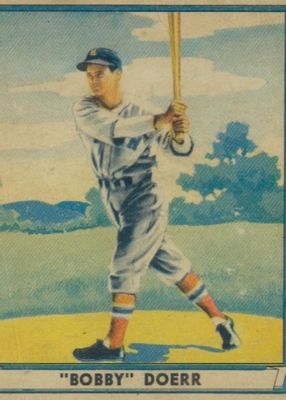

I also love these old cards. It’s such a beautiful representation of the game and the player. The color and artwork is wonderful, and feels so, well, Golden Age.

He may have been the silent type, but he made his noise on the diamond. He was a key part of the Tiger’s World Series winning team in 1935. Gehringer had six All-Star selections. He was the AL MVP in 1937 when he led the league with a .371 batting average. He had over 200 hits in seven different seasons and was third all time in hits for a second baseman. For his career he had 2,839 hits, with a .320 career batting average and .404 career OBP. His 574 career doubles are second all time at second base, and twenty-fifth in MLB history.

Gehringer was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1949. His number 2 was retired by the Detroit Tigers in 1983.

Charlie Gehringer passed away in 1993 at 89 years old.

Number 3:

Red Schoendienst had the right nickname. Cardinal’s baseball was a part of his DNA, his blood ran red, well I guess all our blood runs red, but his was Cardinal’s red. He was involved in baseball for seventy-six years as a player, a coach and a manager. Seventy-six years! That’s insane, but even more insane is that he had served sixty-seven of those with the Cardinals. As a player he wore uniform number 2 for fourteen of his nineteen years in the Majors. He also wore it while coaching and managing for a total of forty-five years! That might be a record, but I haven’t really looked at managing and coaching and probably won’t unless it’s relevant to the player (If you know this, let me know!) Either way, Red=2.

Even though it’s a manager card, I choose his 1969 Topps because his number 2 is so prominently displayed. I also thought it fitting since most of his time in the Majors was coaching, managing or administrative. It’s also a damn nice-looking card.

Schoendienst played second base for nineteen years in the Majors. He was with the Cardinals for the first twelve before being traded to the New York Giants in 1956. To say the trade was unpopular would be an understatement. He would only play one season with the Giants before being sent to the Milwaukee Braves. He eventually found his way back to the Cardinals from ’61 to ’63 as a player/coach.

Schoendienst was a ten-time All-Star. He led the NL in stolen bases in 1945 and was a staunch defender, leading NL second baseman in defense seven seasons straight, including going 320 consecutive chances without an error. He held the record for fielding percentage in a season at second for thirty years until Ryne Sandberg broke it. He won five World Series Rings. His first with the Cardinals in 1946 when they beat the Red Sox. The second was ’57 with the Braves, then again with the Cards in ’64 and as their manager in ’67, and coach in ’82.

Schoendienst would finish his career was a 44.8 WAR, .289 batting average with 2,449 hits. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1989. He is also a member of the Cardinals Hall of Fame and his number 2 was retired by the Cardinals in 1996.

Red Schoendienst passed away in June of 2018 at the age of 95 years.

Number 4:

Nellie Fox had the vision of a hawk (or maybe a fox, Do they have good vision?). Regardless, he knew how to get the bat on the ball. This guy could not miss. For his career he struck out only 216 times in 10,351 plate appearances, good for 5th all time. In his nineteen seasons he never had more than 18 strikeouts in a season and once had more triples (12) than strikeouts (11). I’ve seen players today strike out eighteen times in a week. He was a pitcher’s worst nightmare.

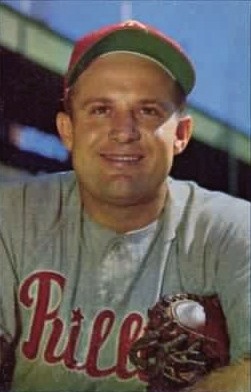

Fox played for nineteen years in the Majors at second base from 1947 to 1965. He started his career with the Philadelphia Athletics but was traded in 1949 to the Chicago White Sox. He would stay with Chicago for fourteen seasons until 1964 when he signed with the Houston Colt .45s to finish his career as a mentor to youngster Joe Morgan. He wore number 2 for fourteen seasons.

I love the 1960 Topps cards with the two side-by-side pictures and that cool White Sox symbol with the wings (Did they drink Red Bull in 1960?). This Fox card was a pleasant surprise because his uniform number is so nicely displayed on his sleeve. Such a great card for the series.

Fox was not a big man. He was only five foot nine and was not a power guy, but as mentioned above, he made up for it in his batting skills and his defensive prowess. He led the league in hits four times, batted over .300 six times and led the league in singles seven years straight. He was an All-Star fifteen times, won three gold gloves and was the AL MVP in 1959.

Fox would finish his career with a 49.3 WAR, .288 career batting average and 2,663 hits. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1997 and his number 2 was retired by the White Sox in 1976

Fox lost his battle to cancer on December 1st, 1975, at only 47 years old.

Number 5:

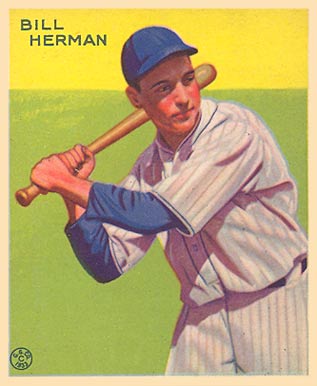

It’s hard to find cards or pictures with uniform numbers showing for some of these old players. Still this 1933 Goudey card is awesome. Like all these Golden Age cards, the colors and pictures are great. Plus, I wanted to represent Billy Herman on the Cubs since that is the only time he wore number 2.

Billy Herman was a second baseman in the Majors for fifteen years. He played from 1931 to 1947, missing two seasons for military service during WWII. He played ten seasons for the Chicago Cubs, then played for the Brooklyn Dodgers, Boston Braves and the Pittsburgh Pirates. He wore number 2 for only five seasons with the Cubs from ’32 to ’36 but had a career WAR of 57.7 which helped him make the list.

Herman had over 200 hits in three seasons and batted over .300 nine times. He was a ten-time All-Star. He played for four World Series teams but never won a ring as a player. He did eventually win a ring with the 1955 Brooklyn Dodgers as a coach.

He ended his career with .304 batting average, 2,345 hits including 486 doubles. He is a member of the Chicago Cubs Hall of Fame and was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1975 through the veterans committee.

He would go on to coach and manage several teams including the Boston Red Sox where he coached from ’60 to ‘64 and managed ’65 and ’66. Not the best years for the Sox.

Herman passed away in 1992 at 83 years old.

Number 6:

I felt this 2013 Topps Update represented Tulowitzki as I always think of him. Wearing a Rockies uniform and making a strong defensive play. It had the added benefit of showing his uniform number as well.

Troy Tulowitzki is currently a coach for the Texas Longhorns college team. He played shortstop for thirteen years in the Majors. He wore uniform number 2 for eleven of those and chose the number due to Derek Jeter being his idol growing up.

He played for the Colorado Rockies from 2006 to 2015 when he was traded to the Toronto Blue Jays. Injuries forced him to miss the entire 2018 season, and he was released by the Blue Jays. He would sign with the Yankees for 2019, but played only five games before being injured again, which eventually led to his retirement.

Tulowitzki was a five-time All-Star, he had 2 Gold Gloves and 2 Silver Slugger awards. He came in second for ROY in 2007 losing to Ryan Braun. He would finish his career with a WAR of 44.8, .290 batting average, 1,391 hits, 225 home runs and 780 RBIs.

Number 7:

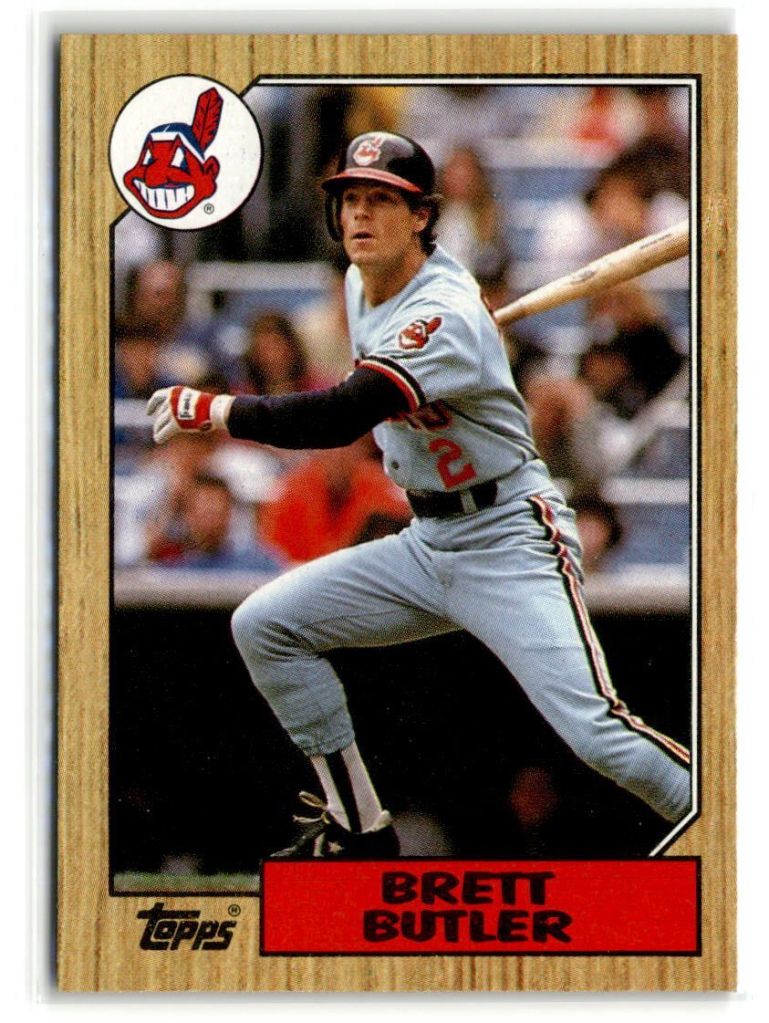

This card alone could have propelled Butler higher. I love the 1987 Topps design, and I know it’s not the best design out there, but it’s nostalgic for me. ’87 is the first year I really got into baseball and card collecting. I had some cards from ’85 and ’86, but by ’87 I was all in. I probably pulled this Brett Butler card dozens of times. It’s a nice card, his uniform number is displayed perfectly, and the photo is great. I’m happy to feature it.

Butler played seventeen years in the Majors as a center fielder. In fact, he is the only outfielder on this list. He played from 1981 to 1997 with the Atlanta Braves, Cleveland Indians, San Francisco Giants, Los Angeles Dodgers, New York Mets and again with the Dodgers. He wore number 2 with the Indians and the Giants.

Butler got his lone All-Star bid in 1991 as a member of the Dodgers. He led the league in runs and walks that season. He also led the league in triples four times in ’83, ’86, ’94 and ’95.

He would finish his career with a 49.7 WAR, .290 batting average, 2,375 hits, 277 doubles, 131 triples and is 25th all time for stolen bases with 558.

Butler would go on to coach in several organizations and would manage a couple of Minor league teams as well.

Final Score:

This is so much fun for me. I hope that there are some folks out there reading these posts and getting just as much enjoyment out of them. I love learning about players, both popular (like Jeter) and not so popular (like Butler). As you can see, although it pains me to put a Yankee in the top spot, my love of baseball and the achievements of some of these players outweighs my Yankee hatred.

For uniform number 2 four of my seven had their numbers retired. Five are in the Hall of Fame. Six of the seven played infield, primarily second base and shortstop. Only Butler played the outfield. Only one (Tulowitzki) is a modern era player. Two played their whole career with one team (Jeter and Gehringer), and one Schoendienst spent a lifetime with the Cardinals.

This was a fun one, as I expect they all will be. A few honorable mentions: The great Jimmie Foxx wore number 2 one season as did Roberto Alomar, Graig Nettles, Darrell Evans, Chet Lemon and Jeff Kent. Mickey Cochrane wore it three years. Current player Xander Bogaerts has worn it twelve years and Alex Bregman ten. Red Sox great Jerry Remy also wore it for ten.

Please let me know if you have any thoughts on the picks. Would you add or replace anyone and why? I love hearing some great baseball discussions.

Make sure to check out the next post with uniform number 3. I don’t even know if I should put Ruth at number 1 or just talk about him since he is the most obvious choice there is. Maybe I’ll pick seven after Ruth. Thanks for joining me!

| PLAYER NAME | YEARS WORN | CAREER WAR | NUMBER RETIRED | OTHER ACHIEVEMENTS |

| Derek Jeter | 20 | 71.3 | Yes (Yankees) | 14x All-Star World Series Champ (96, 98, 99, 00, 09) ROY (96) 5x Gold Glove 5x Silver Slugger HOF (20) |

| Charlie Gehringer | 11 | 84.8 | Yes (Tigers) | 6x All-Star MVP (37) HOF (49) World Series Champ (35) |

| Red Schoendienst | 14 (45 total including coach and manager) * | 44.8 | Yes (Cardinals) | 10x All-Star World Series Champ (P46,57,64 C/M 67, 82) HOF (89) |

| Nellie Fox | 13 | 49.3 | Yes (White Sox) | 15x All-Star AL MVP (59) 3x Gold Glove HOF (97) |

| Billy Herman | 5 | 57.7 | no | 10x All-Star World Series Champ (C 55) HOF (75) |

| Troy Tulowitzki | 11 | 44.8 | no | 5x All-Star 2x Gold Glove 2x Silver Slugger |

| Brett Butler | 7 | 49.7 | no | 1x All-Star |

Sources:

Bak, Richard (1991). Cobb Would Have Caught It. Wayne State University Press. pp. 190–207. ISBN 978-0814323564.

https://www.baseball-almanac.com/

https://www.baseball-reference.com/

Shout out to all the cool cards and creative commons for my pictures! Thanks Topps and Upper Deck and Fleer and Donruss!