Posted April 17th, 2025 by jake

I was playing pickleball the other day, and this older man came over to be my partner. He explained that he was probably going to need a bit of help as he was not too quick on his feet. He was 85, and while he struggled a little to get to some balls, his reaction time at the kitchen was insane, he had a great serve and could dink with the best of them. We didn’t win, but man he was funny, and we had a blast. His friend who brought him was very grateful that I played with him, and I said “anytime”. I’m no pro, I’m out there to have fun, and he made it fun. He was full of energy and humor. I realized, this is someone I would like to emulate as I get older. I hope I’m able to get out, meet new people and play a sport when I’m that age. This got me to research some of the oldest to players in the Major Leagues and it was quite the list of interesting feats.

From Satchel Paige striking out a batter at nearly 60 for the Kansas City As in 1965 to Julio Franco smacking a home run for the New York Mets at almost 49 years old in 2006, there are many age defying stories to be told. In life age is just a number, and one player who proved this in seven different decades was Minnie Miñoso.

Minnie Miñoso was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2022. Minoso passed away in 2015 at the age of 90-92 years old depending on the birthday you use. I want to add a disclaimer here. I’ve noticed some discrepancies with Miñoso’s age and date-of-birth in a few different articles. It would seem there was some confusion as to his actual age and birth year. I’ve been going on November 29th, 1923, a date that you find almost everywhere. So, if sometimes his age seems off, you may be right.

At the induction, his family were on hand to receive the honors and his wife, Sharon Rice- Miñoso, spoke on his behalf. He was elected through the Golden Days Era Committee along with Jim Kaat, Tony Oliva and Gil Hodges. It was a beautiful summer day. I remember it well. I was there, along with my uncle and cousins. As lifelong Red Sox fans, we made the trip to Cooperstown for David Ortiz, and it was an all-around awesome experience.

One of the facts that struck me about Miñoso was that he played in seven different decades, though some of the at-bats were for promotional purposes, I still thought it was pretty cool. He made plate appearances in the 1940’s in his home country of Cuba and eventually for the New York Cubans of the Negro National League, winning a World Series with them in 1947 and becoming a two-time Negro League’s All Star.

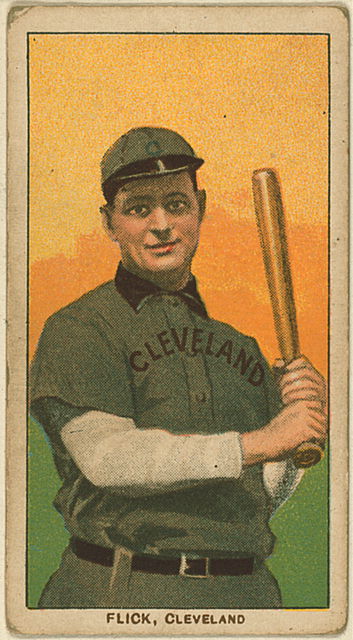

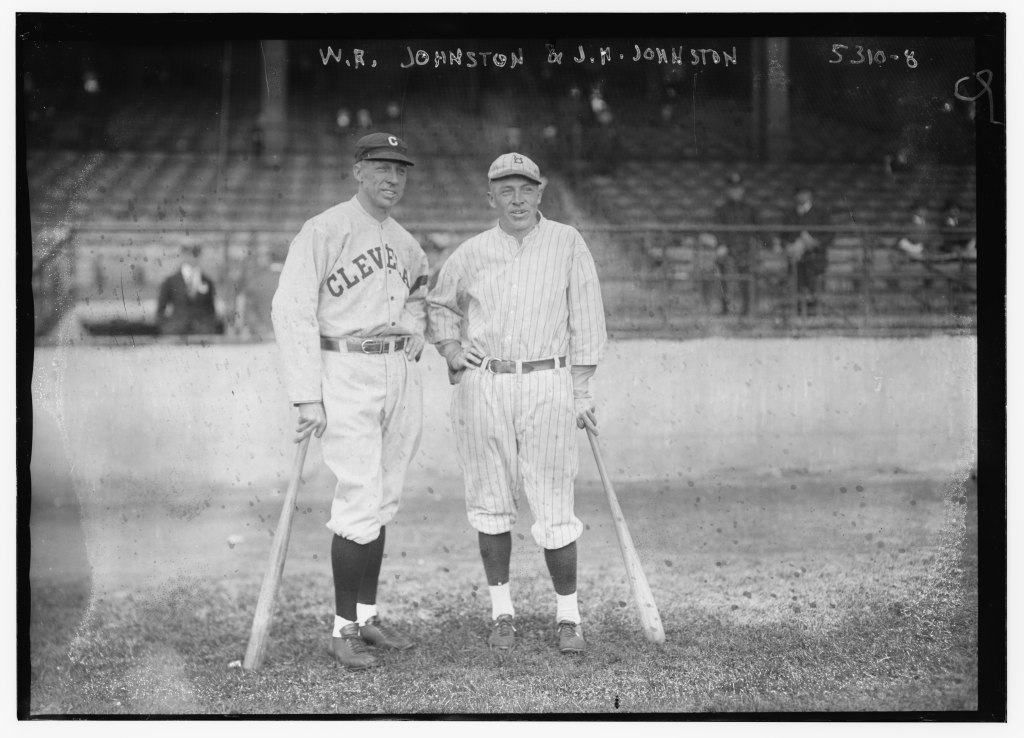

The next year, 1948, he signed on with the Cleveland Indians. He would only play in 9 games before being sent to the minors in San Diego for additional conditioning. He played well in San Diego, hitting for a .297 average with 22 homers, 19 doubles and 13 stolen bases in 137 games in 1949, then in 167 games in 1950, he had 203 hits and batted .339 with 130 runs, 40 doubles, 10 triples, 20 home runs and 115 RBIs, plus he also stole 30 bases. Miñoso showed all the skills of a future All Star and in 1951 he was promoted to the Majors.

Unfortunately, he would only play in 8 games for Cleveland. This had nothing to do with his skill or potential, but was due to a lack of open spots in which to play him. I said unfortunately, but not for Miñoso…for Cleveland. They would trade him to the Chicago White Sox where he would play for the next 6 seasons, becoming an instant All Star.

Miñoso was the first black player for the White Sox and the fans loved him, even giving the rookie his own day and the nickname “Mr. White Sox”. He would play 138 games for Chicago in 1951, batting an outstanding .324 with 32 doubles, 14 triples (most in the MLB), 10 home runs and 31 stolen bases. He was known to crowd the plate, and he was plunked a league-leading 16 times, frustrating opposing pitchers. He would make the first of his 7 All Star team appearances (as one of the first Latin Americans to be named All Star) and he would finish 2nd in AL Rookie of the Year voting and 4th for MVP.

Miñoso was just getting started. After his spectacular rookie season “Mr. White Sox” would continue to wow the Comiskey Park fans. He was an All Star again in 1952, 1953 and 1954. Having had arguably his best season with the White Sox in 1954 batting .320 with 182 hits, 29 doubles, a league leading 18 triples and 19 home runs with 116 RBI’s, he also stole 18 bases.

Miñoso was a character both off and on the field. Driving around Chicago in his green Cadillac, flashy cloths and jewelry, and big hats, he continued to live up to his nickname, “Mr. White Sox”.

In 1957, Miñoso had another All-Star season. He ended up with 21 home runs (the most he had hit up until that point) and led the league in doubles with 36 while also hitting .310. But the White Sox were desperate to win, having continuously been bested by the Yankees, and were offered a trade that they just couldn’t pass up. In the off season, Cleveland offered up Al Smith, who was a quality player with youth on his side, and pitcher Early Wynn, who would go on to have a Hall of Fame career, for Miñoso, and “Mr. White Sox” left the windy city.

Miñoso was back with Cleveland in 1958, and had a solid season with 168 hits, 94 runs, and 14 stolen bases (though he was also caught stealing 14 times). He also hit the most home runs of his career with 24, to go along with 80 RBIs, 25 doubles and a .302 batting average. I mentioned earlier researching those who defied the age barrier, well by 1958 Miñoso was 34 years old, and he had the most home runs of his career!

In 1959, he was once again an All Star, hammering 21 home runs and finishing the season with a .302 batting average. Cleveland finished five games back behind Miñoso’s former White Sox, who made a trade in the off season to bring Miñoso back to Chicago.

In 1960, he entered his 3rd decade playing ball. He was now 36 years old and started the decade off with a bang. Once again with the White Sox, he played in 154 games and made the All-Star team again. He led the league in hits with 184, and had 34 doubles, 20 home runs and 105 RBIs to go along with a .311 batting average. “Mr. White Sox” was back, and the fans were ecstatic!

In 1961, the White Sox struggled to a fourth-place finish. Miñoso had another productive season. He played in 152 games and had a .280 batting average with 151 hits, 28 doubles and 14 home runs. Unfortunately, it would be his last productive season in the Majors. He was traded to the Cardinals but only played 39 games in 1962 due to injuries. He was then sent off to the Washington Senators in 1963 and played 109 games as the fourth outfielder. In 1964, he found his way back to the White Sox but only played 30 games.

Though he was slowing down, at 40 he decided to play in Mexico, and had a resurgence. He batted .360 and led the league with 106 runs and 35 doubles for Charros de Jalisco in 1965. He would continue to play baseball for 8 more years in Mexico, bringing him into his fourth decade. He would finally leave the game in 1973 at 49 years old…or so it seemed.

He would become a coach for the White Sox in 1976 and appeared as a DH in 3 games with Chicago. In 8 at bats, he would only get one hit, but was still a favorite of the White Sox fans. He continued to coach through 1978.

In 1980, he would amazingly get two more at bats with the White Sox. He was around 56 by this point, depending on which date of birth you use, and became one of only two players to have played a game in five decades! The other being Nick Altrock, who remains the oldest player ever to hit a triple at age 48 in 1924. Altrock played his last game in 1933 at 57 years old, but Miñoso would top that.

Miñoso didn’t suit up again for 13 years. In 1993, at 69 (I know this is getting ridiculous now!), he signed with the Saint Paul Saints. This would seem to be more of a promotional stunt, but according to Michael Clair of MLB.com, “Mike Veeck, the owner of Saint Paul, made it clear that this wasn’t just a promotion to get fans into the gates and that a baseball player, especially one like Miñoso, would not do anything to embarrass himself. “I don’t think of it as a promotion, I think that’s an appearance of talent,” Veeck told MLB.com. “That’s how I view it — it’s an opportunity for these younger fans, and for fans who enjoy them to see this remarkable human who all these years later could still swing the bat, who still hustled out to first base.” (Clair, Micheal, MLB.com, 2021)

Miñoso got one live at bat, and made contact, grounding out. This would be his sixth decade, and the bat and ball are now enshrined at Cooperstown. Six decades, and he made contact with the ball, at 70! I wish.

His seventh decade was also with the Saints. This time in 2003 at the young age of 79. He signed a one-day contract and walked in his only at-bat. This made him the only player to have played in seven decades.

Miñoso had a career WAR of 53.2 with 2113 hits, 195 home runs, 365 doubles, 95 triples, 1089 RBIs, 216 stolen bases and a career .299 batting average. He was a 9x All Star and was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2022, 7 years after his death in 2015 at 90 something depending on the date of birth. I’m going with 91. His number 9 was retired by the White Sox in 1983.

“Once you get (baseball) in your blood, you can never quit,” “I love the game.” Minnie Miñoso, via the Daily Sentinel, 1976

Sources:

https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/m/minosmi01.shtml retrived April 2025

Clair, Michael. “Miñoso’s amazing seven-decade career.” MLB.com, February 2021

Livacari, Gary. “Minnie Minoso’s “Grand” Return to the White Sox, 1960!,” baseballhistorycomesalive.com, February 2022

Muder, Craig. “Miñoso defies time as White Sox’s DH,” baseballhall.org, retrieved April 2025

Stewart, Mark. “Minnie Miñoso,” SABR bio, December 2021

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minnie_Mi%C3%B1oso retrieved April 2025